INTRODUCTION

A well-functioning city is a wonderful place to be. Cities such as London, Boston, and San Francisco have a great feel to them because there is a balance of consistency and variety that allows for a wide variety of housing solutions to occur. Economic stability helps as well. However, those cities went through their most formative years over 100 years ago. Young urban areas such as Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Dallas struggle to create thriving urban areas with consistency. One reason is a serious lack of housing choices. And when typologies come together in sprawling cities, there is often strange transitions from single-family houses to mid-rise (or even hi-rise) urban areas because they follow a very stringent formula of density and scale.

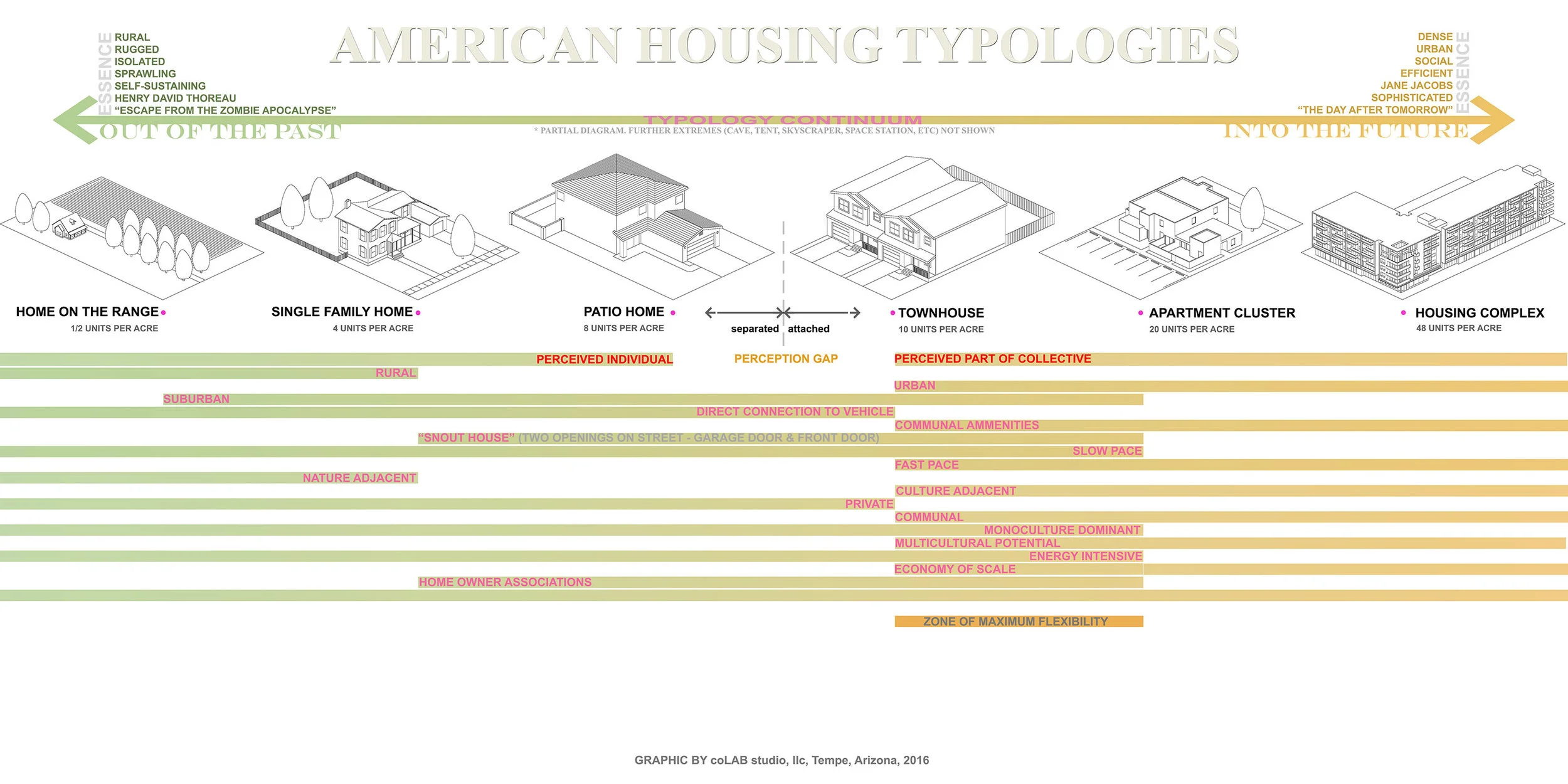

Young city housing typologies in the US stick to a script of 6-7 versions (see diagram below). The lack of choice in typologies leaves us with far less choice in where and how we live. Without better options, two major consequences have created ongoing difficulties for such cities: First, people tend not to interact with their communities because they do not live in any home for long; Second, thriving urban zones in and around neighborhoods do not form organically as easily as other more established cities. Though these social and urban problems may have additional causes, the lack of available housing types have contributed to them and other issues.

We are often asked questions about housing within Phoenix: Why are there so many rentals being built and so few for purchase? Why is there nothing being built for low-income singles? Why does everything look the same? Why is this street getting all the attention right now while two blocks away there are no plans for development? All good questions.

This paper will attempt to answer these questions and cover why we have such limited choices when it comes to housing types, the effects of those limitations, and what it might take to create change. Some of the statements along the way may seem rather sweeping, however such generalizations are helpful for raising conversation on the problem within this short medium. A good sized book would be required to answer such questions in detail. We will back up some statements with links to online articles where possible. It is important to remember this paper’s discussion is based around newer and larger suburban cities such as Phoenix, Dallas, Houston, and Salt Lake City. Though many of the same issues apply to smaller and sometimes more “hip” cities such as Portland, Tucson, and Austin as well.

EFFECTS OF LIMITED HOUSING OPTIONS

Once upon a time suburban homes were a repeatable solution to the fairly severe post-war housing need. Traditional families, with two parents and two-to-four children were, well… normal. But today with people working out of their homes (Mike Brady: Home work-force pioneer!), live-work-commerce models, “non-traditional” families, boomerang generation trends, and the massive rise in single-living many of the traditional models for housing types have become fairly obsolete. Aside from currently trendy but very limited access to micro-dwellings and the small-house movement attracting interest from singles, the models for housing types most often built are out-of-sync with contemporary living needs. Whether you are a single artist, a stay-at-home 3D printing manufacturer, a LBGT couple, or multi-generational family, a typical 3-bedroom house with its standard wall placement and structural configuration is often considered inflexible for a wide variety of required uses. And it is often very difficult to find housing types that fit those uses and needs. Let’s look at a diagram of typical housing:

As already mentioned, there are the six basic housing typologies in most cities, listed here at their most common density levels. The diagram demonstrates several important points:

1. There is a clear division between attached and separated unit types. Other research coLAB has conducted indicates there is a large population of people who cannot envision themselves living in attached housing of any kind. This is why single-family housing (SFH) is still so popular. And because of rising land and construction costs, the way to make them more affordable is to build “patio-homes,” which have none of the positive value of traditionally rural SFH and all of the negative effects of sprawl (poor health, long commute times, inefficient energy use, social isolationism, etc). Still, studies believe that over 50% of all Americans live in suburban single family homes.

2. Because of growing populations, increasing construction costs, shrinking available land in most cases, and growing awareness for the importance of living in balance with the environment, cities should be building with greater density.

3. #1 and #2 above are at odds with each other.

4. None of these models automatically provide the required space-flexibility for non-traditional modes of living. All are built with fixed walls set up for maximum bedrooms with traditional living spaces, though often homes and apartments are now built with slightly more flexible “great rooms” that combine living, dining, and kitchen. However, most fixed walls in most housing developments are structural and offer barriers to renovation while still disabling further flexibility of use and function.

5. The most positive overlap of different types of lifestyles occurs at the “townhouse” and “apartment cluster” scales and densities. This could indicate a good place to start looking for new typologies with greater flexibility.

These building types are also so specific they may lead to abrupt transitions between types. The worst case scenario I can think of is a 20 story condo building where my grandparents lived in Westwood, California, which looked over a couple of two-story apartment clusters and a vast neighborhood of single-family houses. The views and spaces were fairly uncomfortable for everyone. Another example I can provide is in my current neighborhood within Tempe, which currently has a five-story apartment complex under construction directly behind single-family housing.

The final effects of these poor transitions produces negative urban spaces and disharmonious psychological effects on the people living among these conditions. In fact there have been many studies that show that these environments create specific psychological and physical health problems. One publication that lists out what positive spatial attributes contribute to positive mind and body responses is 14 Patterns of Biophillic Design by Terrapin Bright Green.

Hudson Manor, Tempe. Photograph by Matthew Salenger.

The discomfort that people feel in sprawling cities, with or without the transitions, seems to result in shorter time periods for people to reside in one place. It is not uncommon for people to move every five years or so when living in sprawl. The shorter one lives in a home, the less connected they are to the neighborhood and community. Greater mobility and isolation occurs. This, in turn, breeds the desire for looking for familiarity with well-known brands, big box stores, “chain” restaurants over locally owned choices. All this contributes to weaker street activation and dull urban areas, which can create huge areas of static growth or even spiraling decay.

CAUSES LEADING TO LIMITED TYPOLOGIES

One would think that with so many people desiring variation and flexibility in housing types more models for living would exist. But there are various controls on what gets built, none of them sinister in nature, but all of them work together to constrict what gets built. One of the most obvious is what people are willing to purchase. And what people are willing to purchase is limited to what they believe they can sell, preferably at a profit. These are part of what we call market forces, and it alters what gets built at the same level of a developer as the individual home buyer/seller. These are some causes of the housing issue:

1. A developer will only build what they can make a profit on (or at least break even if they are the rare non-profit type). They seek to develop what the current buyer wants, usually based on historical data of what has made money in the recent past, and then guess what will garner a higher price based on trends. They take into consideration what land costs are and what typology of building will be possible (by zoning and neighborhood) and test its economic viability through design and/or pro forma (number crunching) models. Experimenting with new typologies is generally seen as risky; both for the developer and the buyer. Thus, this isn’t just on the developer, it’s on “us,” the consumer as well. These are some of the ways in which “market forces” work to decide what, where, when, and how housing developments get built.

Developers also prefer to stick to their scripts on the aesthetics of developments. Units are often of a similar size from project to project, which makes for the repeated exterior appearances of nearly all 4-6 story developments. They can alter the materials they clad the building in, but they hardly ever have a different presence from the street.

Land costs often dictate where developers build, choosing areas with lower land next to higher property values with proper zoning (see #3 below). For years the land costs have been higher than they should be, necessitating developers build rental units over for-ownership models in order to bring in long-term money to cover the higher initial costs.

2. A huge reason for limited typologies lies with financial institutions who finance construction projects. Banks are notoriously conservative, and base many of their decisions on historical models of given typologies. There is a lot of data on the most familiar types of developments such as typical five story blocks of housing or sprawling single-family houses on the outskirts of town. There is little confidence from banks on any new and creative typologies someone might want to create, so the developers find it difficult or impossible to find financing for anything other than the familiar/traditional types of housing. Banks are also currently more eager to loan to larger/proven national development companies offering high-end rental units near downtown areas which we see so much of today. For-ownership models are more risky because the financial gain is more short-term and limited.

3. Zoning, the establishment of local districts for certain uses, is a huge factor in deciding what gets built and where it can be situated. Municipalities designate zoning based on what is the perceived best interest of the public. Heralded as a great accomplishment more than 100 years ago, when factories would pollute the air and water directly next to worker housing, it has gotten very prescriptive in the last forty years or so. Zoning mostly prescribes various building densities (how many homes per acre, for instance), and uses (housing vs commercial vs industrial).

Municipalities often want to increase density in order to make civic service (fire and police), utility, and transportation infrastructure more efficient. Greater density provides increased tax revenue per acre, which is a benefit to the city’s ability to function- but also often for the population. Having more people per acre provides better commercial services for residents (as long as it is zoned appropriately) as walkability improves. When a town wants to increase density, it revises zoning to allow for greater density, and usually eliminates less density in an area. This is when you get 5-7 story buildings or even high-rises next to single-family homes.

Some municipalities don’t even allow for anything in between. We recently discovered that Scottsdale, Arizona, for instance, doesn’t allow townhouses that act as single-family houses for ownership (as opposed to rental units) as an in-between density level. They also don’t allow clusters of attached houses. They used to allow these typologies, but likely eliminated them thinking such typologies damaged a standard of living or lowered adjacent property values.

4. Another deciding factor is how government gets involved. Prior to the 1970s, banks in the US would generally not loan to non-whites or females because they were traditionally seen as “high risk.” Congress helped to set up government backed loans for such people to equalize the loaning industry. After World War II, government also started to support development of low-income (or “socialized”) housing- sometimes with rather disastrous results. While these interventions have had their flaws, they at least recognize the need for assistance for those that do not have purchasing power within standard market forces. Without them, home ownership for a majority of people would likely not exist at all.

There are many limits on what government can do to level the housing playing field, and it is not evenly governed from state to state. In Arizona, for example, the state legislature has ruled out many options for its municipalities to provide for better urban environments. Tax Increment Financing (TIF) to provide subsidies for such low-income projects is outlawed, as is mandating percentages of any development to provide for low-income housing. These restrictions are unique to Arizona, along with the recent meddling with Business Improvement Districts that allow an area to self-govern for greater improvement than municipalities provide. Though proven successful in other states, these tools have been removed from use in Arizona because of a strong belief in the market to cure all ills on its own. Though Arizona has a relatively low cost of living in the state, the current low wages and little incentive to build for diversity in urban areas, there is a location separation of the wealthy from those that must “drive till they qualify” out to the edges of town where sprawling developments so often occur.

This can be a trap for people with lower incomes, as the long drive times means there are few public transportation options, leaving them beholden to their private vehicles at greater cost than if they could live closer to urban areas where most of the jobs are. The neighborhoods, too, do not escalate in value as quickly as most other areas, meaning they don’t have the chance to build up as much wealth.

POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

Though there are strong forces that create the limited housing typologies we have, there are possible solutions we can be working towards to create real and lasting change.

1. Municipalities can push developers to be more creative. Municipalities should have design review boards that contain industry professionals who understand the issues, are endowed with power that goes beyond just “checking boxes,” and are accountable to the public. They should be able to recognize good creative design and not punish projects that stray from the norm. They could offer more European style competitions or design assistance with positive case-study examples developers might work with.

2. There needs to be better education of financial institutions so they begin to feel more comfortable providing loans to more diverse projects. This requires utilizing housing types from other cities, states, or nations that have proven historically viable. Developers may also have to find creative ways to compare a desired typology model to something more standard in order to convince banks towards what is desired. Working with local banks with more community ties is always a good idea, and in some cases new private or public institutions could be created, such as state banks.

3. Changes to zoning, to allow for more flexibility, could also help considerably. In some cities, there have been changes away from traditional models to what is called the Form Based Code. This is zoning that uses physical form rather than separation of uses and densities. These often still contain flaws, so with either format errors should be noted and improvements should be requested.

4. Government rules and regulations are the most difficult issue to fix, though not impossible. Even in Arizona, there is movement towards getting a state legislature vote on TIF’s. However, regulation, in any form, often has negative consequences. Rules, or their abandonment, should be carefully considered and examples from other states should be studied. But with enough support, the right tools can be implemented.

Each of these potential solutions require a lot of advocacy from industry professionals, professional associations, affiliates, and the general public. For a lot of us, that may be as simple as acting the part of a good “consumer,” and tell developers we don’t like the choices we have. Housing developers want to provide what we will actually purchase, so let them know how to best serve you.

SYNOPSIS

Within a lot of sprawling cities, such as Phoenix, there exist many acres of empty land waiting to be developed. If we want a vibrant city with a sustainable economy and thriving cultural events, we desperately need more housing types that provide for more community diversity. To see those types develop, we need to recognize the forces limiting our choices and work in the right directions to create the change we want. You can start by telling this developer, vali homes, what you are looking for in a home. They are working on new development models in the Phoenix area and would love to hear from you. More than anything, get involved in your community, educate yourself on the issues, and be vocal.